I grew up reading the ‘Little House on the Prairie’ books by Laura Ingalls Wilder. I have a clear memory of sitting on the front porch when I was in grade 2, reading ‘Little House in the Big Woods’ and being enthralled. I worked my way through the list but got bored when she reached teenage years and I stopped reading them. Fortunately, I picked them up again once I reached high school and devoured the whole series all over again.

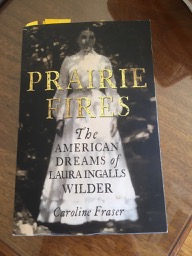

I have no idea how often I’ve read these books, but it would be a very large number. Last year my sister Kate scored me in the family Kris Kringle and she went with a friend to a bookshop to get something. Her friend is a reader and was suggesting this novel and that novel while Kate dithered, not knowing what I’d like. Then she saw this biography of Laura Ingalls Wilder and said, “THIS is one Frogdancer will like!”

She was correct. I polished it off in two days. But something struck me as I was reading it. The lessons of personal finance hold true no matter which era you’re living in.

Debt was the scourge of Laura’s married life. It wasn’t until very late in her life that she and her husband, Almanzo, were financially secure. See these quotes from the book about their first farm, which they moved into at the end of ‘These Happy Golden Years’:

- Before [Almanzo] owned a mowing machine, he had to pay threshers and hire workers to cut his hay and wheat. After selling 95 bushels of wheat and setting another 80 aside for seed, he had ” a little over $40 to live on for another year.” At a time when an unskilled labourer could expect to make over $400 a year, this was unsustainable.

- Expecting their first child in December, the Wilders now found themselves in financial straits. Notes on the farm machinery were due, and they needed to buy coal for winter and seed for next year’s crop. It was at this moment that Almanzo revealed to his wife the debt on their new house: an additional five hundred dollars that she had not known about. That was a small fortune to them, worth over thirteen thousand dollars today. Laura was crushed by the news.

The danger of counting one’s chickens before they’re hatched is just as dangerous today as it was back then. Carrying too much debt puts people in an incredible risky place. The quote goes on to say:

- The fact that her husband had kept this debt from her – he hadn’t wanted to bother her with it, he said – comes up again and again in Wilder’s drafts and letters. It affected her deeply, and for many years. It still rankled when she was writing her memoir, Pioneer Girl, in 1930: “I was to learn that we owed $500 on the house, which we were never able to pay until we sold the farm.” In her manuscript from several years later she was even more pointed, squarely placing the blame on her husband and saying that she had started to wonder” how much could she depend on Manly’s judgement.”

Money fights and money issues are supposed to be the biggest reasons people split up. Even though the Wilders stayed together, it’s obvious that this all put an enormous strain on their relationship.

Laura was 19 when all of this was going on. A few years later, her parents Charles and Caroline Ingalls had to make a decision.

- …Charles Ingalls’ struggles with farming were over. In February 1892, he had sold the De Smet homestead for $1,200 and moved his family to town. The sale, however, dd not represent much of a gain; after the mortgage was subtracted from the total, he was left with $400. Like so many thousands of others, he had succeeded on paper, proving up and claiming the land. But he could not make a living as a farmer. For a man who preferred open, unpopulated spaces, it must have felt like defeat.

Decades later, their granddaughter wrote about them at this stage of their lives:

- It may have seemed, Rose wrote later, that calamities had befallen the Ingalls at every turn, but she recalled them as sublimely content with their lot. “The truth is that they didn’t expect much in this world”, she wrote, “and they just shed thankfulness around them for what they had.”

Being content and thankful for what you have, instead of fruitlessly wishing for things that can never be, is key to living a happy life. By all means, strive for things that you want, but also notice and focus on the people and things around you. It makes you far happier, and also probably far nicer to be around!

When recessions/depressions hit, people go bananas:

- “Ruin seems to be impending over all,” Henry Adams wrote at the beginning of the Panic of 1893…”If you owe money, pay it; if you are owed money, get it; if you can economise, do it; and if anyone can be induced to buy anything, sell it. Everyone is in a blue fit of terror and each individual thinks himself more ruined than his neighbour.”

- He was thinking of his own social class, but no person in America would instinctively heed that counsel more closely than Laura Wilder. Over the coming years, struggling with the constraints of poverty, she would step by cautious step seize control of their circumstances. She would prove adept not merely at penny-pinching, but at finding ingenious ways to generate income, husband their minuscule resources, and protect their assets. As in the schoolyard, she would assume the role of leader, guiding the family on the long and taxing climb to security.

I love this quote. Anyone who’s been in the position of having to scrape together every penny and slowly haul the family out of the pit of poverty will find that this resonates. I’ve had my experience with it and I tip my hat to Laura and her grit and determination.

Forty years later, Laura had a similar economic situation to live through. The economy moves in cycles. This time, she showed that she had learned from her previous experiences.

- “… the economic apocalypse was upon them. In the first week of 1933, [Laura] scraped together all the money she could find and paid off the outstanding balance on the federal farm loan on Rocky Ridge: $811.65c. This time, no matter what happened, she would not lose the farm. She was left with around $50 in cash.

I had a similar experience when I paid off our first house. I logged on one morning and realised I had $10 more in savings than I had owing on the mortgage. I knew we’d have a lean few months until I built my emergency fund back up again, but I couldn’t resist the siren call of being debt-free. Both Laura and I were looking for security for our families.

However, by 1939 the Wilders’ financial affairs had stabilised, thanks in no small part to Laura’s side hustle of writing the ‘Little House’ books.

- While continuing to economise by writing on the backs of old letters and burning wood rather than running the furnace, [Laura] was finally achieving a sense of security. She told her daughter that she had escaped from the nightmare that once troubled her: “I haven’t gone alone down that long, dark road I used to dream of, for a long time,” she wrote. “The last time I saw it stretching ahead of me, I said in my dream,’ But I don’t have to go through those dark woods, I don’t have to go that way. ‘ And I turned away from it. We are living inside our income and I don’t have to worry about the bills.”

However, it wasn’t all fun and games. The Wilders had only one child, their daughter Rose. Over time, they fell into a bewildering financial spider’s web with loans and payments and counter-loans gradually sinking into a chaotic mess:

- Earning a salary from the Red Cross and income as a freelancer, [Rose] made a commitment to her parents to furnish them with a payment of $500 a year, so they could retire from farm work… How badly they needed it is difficult to judge, in the absence of almost any records dealing with the Wilders’ finances. [Laura] was fifty-three, working at two paying jobs. Almanzo, with his disability, doubtless finding it increasingly arduous to plough, care for livestock and do the hundred other tasks involved in maintaining farm equipment, fields and fruit trees. Certainly they needed money, but they may not have required that much. Indeed, they pointed out to [Rose] that they had a comfortable home and plenty to eat.

I suppose it’s nice that her heart was in the right place. However, Rose’s money management skills were appallingly bad. She ranged from what seems like insane levels of expenditure when times were good to living like a pauper when the funds ran out. She’d send money to her parents, (often moaning bitterly about it in letters to friends, even though it was all her idea to do so), and then she’d borrow back money from her parents. By 1924:

- By this point, the question of who was supporting whom was hopelessly entangled. It was becoming impossible for the Wilders or their daughter to extricate themselves, even if they wanted to.

I guess the lesson here is to not lend money to family, or go guarantor on loans. It can get very messy and can ruin what should be close family relationships. Don’t over-commit yourself financially to anything, no matter how generous you want to be. Unlike Rose, make sure your own financial house is in order before you try and help anyone else.

Thankfully, after a lifetime of struggle, both the Ingalls family and the Wilder family ended their lives in peace and security. ‘Prairie Fires’ by Caroline Fraser not only looks at Laura’s life, but Fraser broadens the focus by looking at the economic, social and political events that were happening at the time, and how all of this impacted Laura’s life. It’s a very interesting read, but it certainly makes me glad I was born here and now, and not back then. Life was a lot tougher!

Thank you for another interesting post. Biographies offer so much. We live in very comfortable times.

Interesting post! I was in a fortunate position that my parents did go guarantor on my investment property loan so that I could avoid LMI. 3 years later they have been released from guarantorship and the house and loan is all mine — but my finances are still hopelessly tied up with their issues! Hoping to disentangle most of it over the next three months though, fingers crossed…