Yesterday we had a day at the resort, just to relax. This concept is something new to me – I never take holidays just to relax. But the day slipped by vey easily with reading, blog writing and a nap.

Today – Good Friday – is our last day of sightseeing before we start the long flight home. This is the day that we see what Zanzibar has to offer in natural surroundings.

We drove down to the southern part of Zanzibar, to the National Park, around 35kms from Stone Town. The ranger told us that Zanzibar is flat, with no rivers, lakes or mountains, just small streams.

The rocks that you can see in the path are actually outcrops of coral. This whole place is a thin layer of soil lying on top of a bed of coral. This area is a true wetland – dig a metre deep and you’ll hit water. Many of the trees are mahogany, though there are some huge mango trees as well.

We began walking through the forest in single file. For once, no one was talking. Suddenly, we were face to face with a couple of monkeys.

This is a Sykes monkey, a relative of the vervet monkeys we saw on the mainland.

His friend was sitting on the forest floor, so close I could almost touch him.

A little further along, we saw this millipede. According to the ranger, the millipedes are the safe ones. It’s the centipedes that’ll kill you.

We saw an anteater, or Elephant Shrew, but it was too far away to photograph well. We also saw a few crabs. This place is in between two seas, and the crabs move across from one to the other.

This is a big tree that has blown over. The ranger showed us how shallow the root system is, because of the layer of coral underneath, stopping deep root systems from forming.

A road divides the forest, and here was a bus, jammed to the gills with people. Even though Good Friday isn’t a Muslim thing, they take Government holidays from Tanzania, so Christmas and Easter are public holidays.

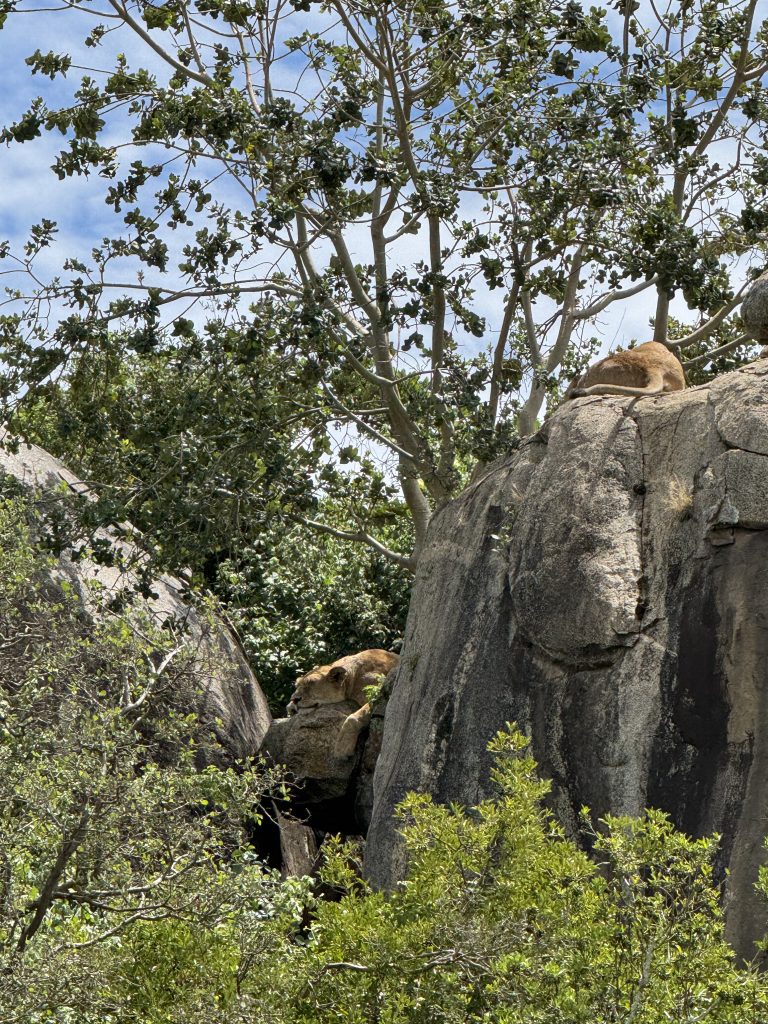

And then I got excited, because we came across a family group of the Zanzibar red colobus monkey. They have 4 fingers and no thumbs. There are 3,000 of them.

They eat leaf shoots, unripe fruit- not ripe fruit because they can’t digest sugar- they have a 4 chambered stomach.

Many more females than males. One dominant male.

The baby moved off on its own, so here it is, almost directly above my head. I was pretty safe … I saw it pee a few minutes earlier.

Peaceful and quiet in their group. “ They lead a good life.”

They look after their babies for 20 months.

We passed this one without realising it, and I only saw it when I glanced back and caught the red of its coat.

This Sykes monkey was close enough to touch, if you were silly enough to try. There was a pool of water in the branch and it was hanging upside down drinking from it when we first walked up.

Like this.

Then it was back in the van to go and see the mangrove swamp.

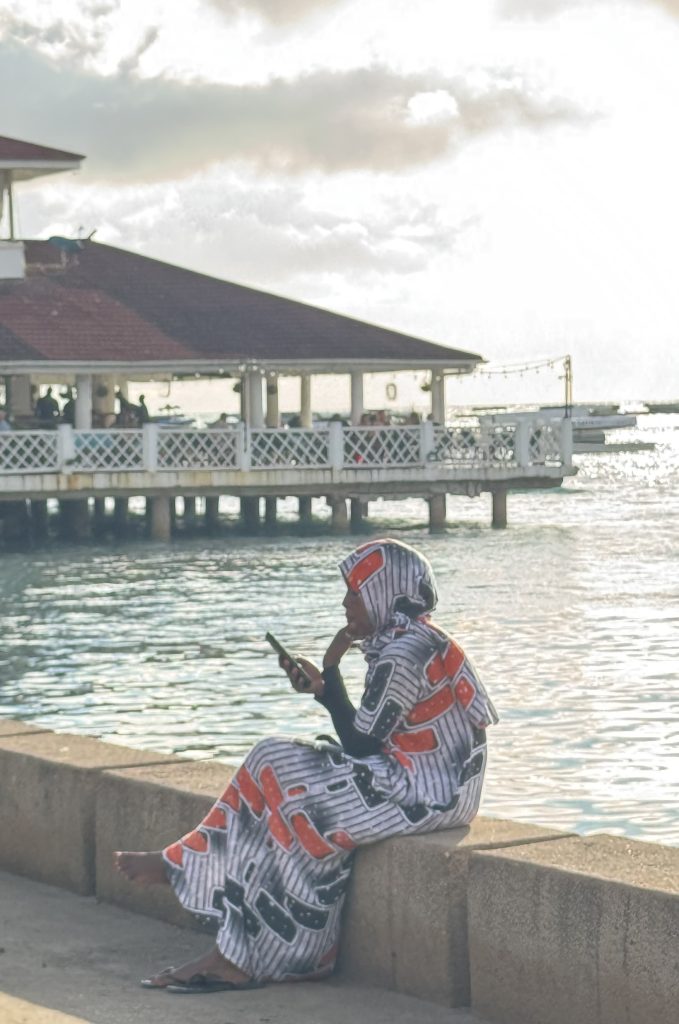

Honestly, this part was pretty boring, but I took a few nice shots of people on the roadside along the way.

Either coming home or going to prayers.

Women collecting firewood. We have it so easy.

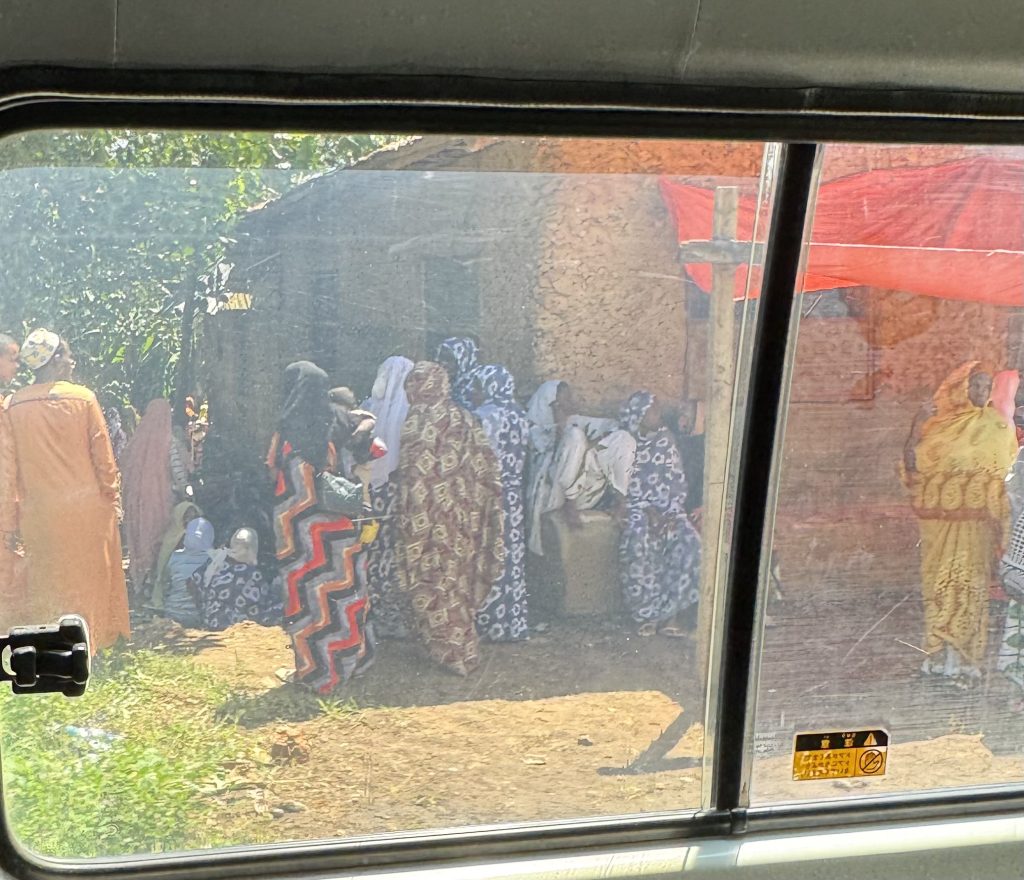

As we were getting back into the van after the mangrove swamp, which I won’t inflict on you, the village was having a get-together. The little girl in the yellow scarf, to the right of the frame, smiled and we waved at each other as I stepped up into my seat.

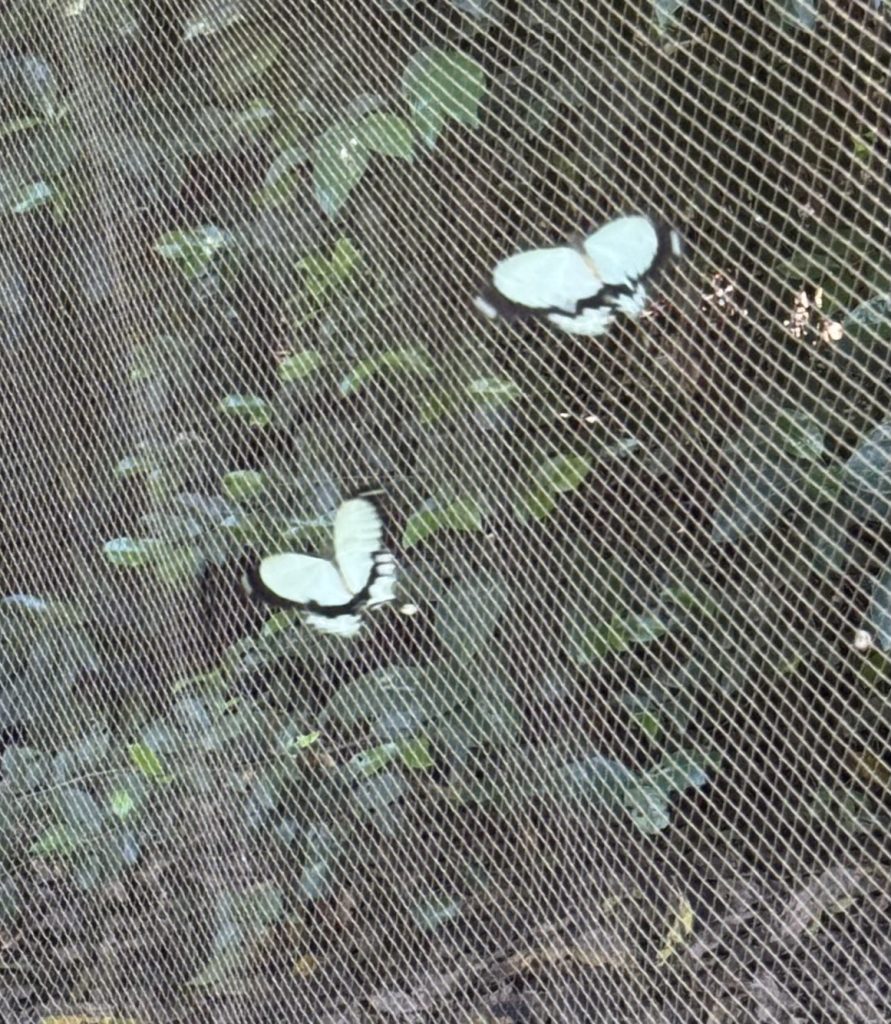

Have you ever heard of a butterfly farm?

18 years ago, a Scottish gentleman whose name escapes me, had the idea to create a tourist attraction using butterflies. Locals are paid for any cocoons they bring in, and this is subsidised by the money tourists pay for admission.

We walked into a big tent, essentially, and saw where they leave the cocoons, ready for the butterflies to break out and enjoy their 2 weeks of life.

They were very frustrating to try and photograph.

Beautiful, but constantly on the move.

Except for this one. It was having a rest.

The guide at this place led us to a little enclosure, saying, “ I have a surprise for you!”

OMG. Chameleons.

Look at his curly tail!

The guide put a grasshopper down so we could see how chameleons hunt.

Fantastic.

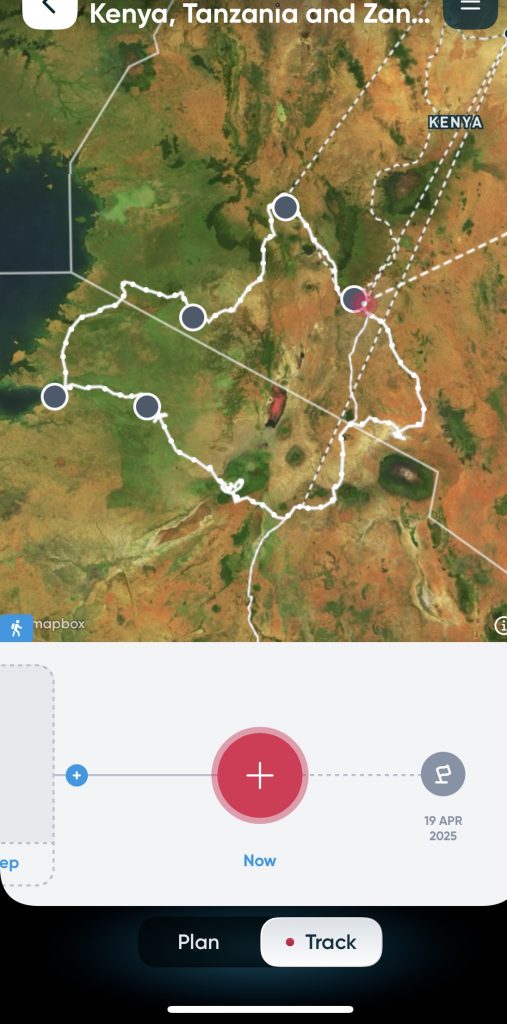

Then it was back to the resort. So far in 2025, I’ve seen rice paddies in Vietnam, Japan, Tanzania and Zanzibar.

Just before I fell asleep, Awaysu called out, “Wedding!”

He said Friday is popular for Muslim weddings, while Christians tend to get married on Sundays.

Annette and I collapsed and had a nap when we got back. The holiday is pretty much over. Tonight and tomorrow we’ll be hanging around the resort until 5 pm, when we’ll be picked up to go to the airport.

P

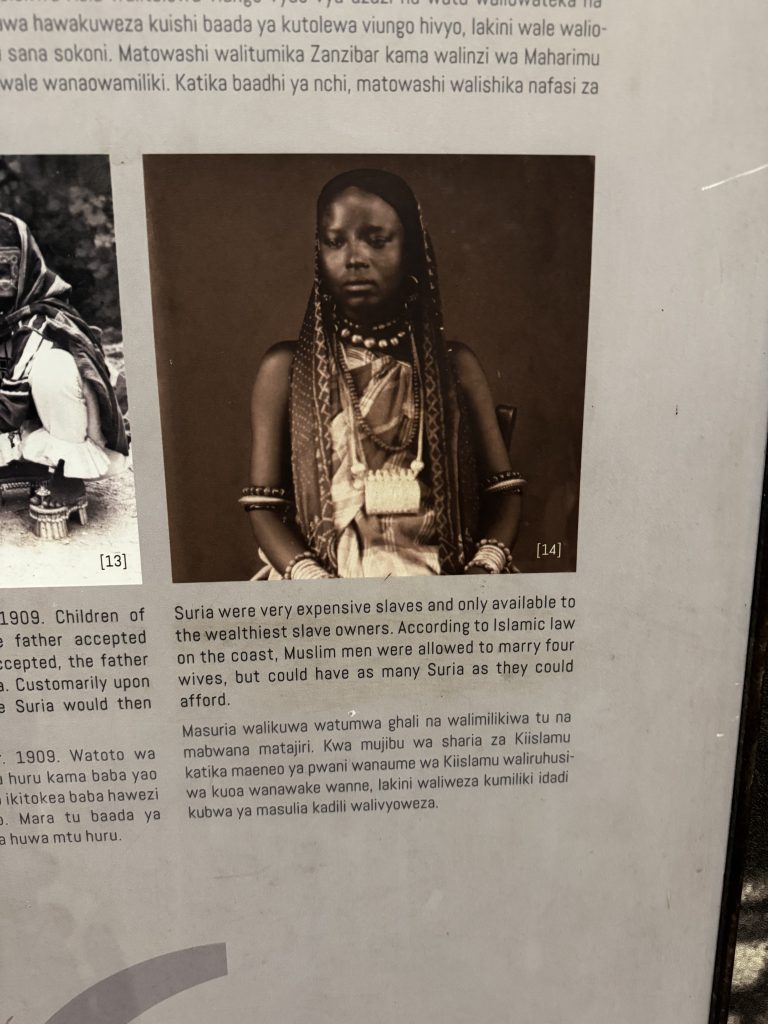

Zanzibar was a different experience than I expected. I didn’t know about its history before I arrived and it affected me profoundly. It is such a tropical paradise, yet for neatly a thousand years its people have been under the heel of one foreign government after another.

Even today, after they had a revolution in 1964 and, in theory at least, were able to self-govern, they joined forces with Tanzania because they knew they weren’t strong enough to stand alone.

The thing that got me? Zanzibar doesn’t have its own electricity supply. It all comes from Tanzania and is very expensive. At any time, Tanzania could flip the switch and Zanzibar would have no electricity.

(Except for the resorts, naturally. They have generators.)

These people have been held back by slavery, foreign governments and religion and they’re still not out from under. It’s made me sad.

But having said that, I’m very glad I came here. It’s a place very much off the beaten track and I’m pleased that I’ve seen it. I’m going home to a parent who is really struggling, health-wise, so having a few days of R & R is probably a good thing.

Unless something exciting happens tomorrow, I’ll see you when I get back!

Dad Joke of the day: